Locating Vitality

—core studio in the 2nd year of the MLA program

Washington University in St. Louis

Spring 2017

The notion of ‘revitalization’ assumes that the sort of vitality we desire in a neighborhood or city is ready-made. In order to recover an urban site—in which something has been lost through a set of processes we often call urban decline—we attempt to import, design, and construct vitality.

What is meant by vitality and how do real estate developers use it to make monetary value where there was little to none before? Who or what is valued in a mode of redevelopment which attempts to reproduce some codified form of vitality? Would we locate vitality in the quasi-prairies of the north side of St. Louis, which emerged due to human absence and civic neglect? Can we see vitality in the self-organized public spaces marginalized people create when they are excluded from gentrified enclaves?

Rather than serving outdated modes of redevelopment by commodifying vitality, this graduate landscape architecture studio attempted to locate vitality in our sites of interest. First, by discussing theoretical texts and via critical touring in St. Louis and Detroit, each student developed their own critical lens. As the class looked, together, at redevelopment schemes and listened to their proprietors, we identified a number of known ways to stimulate urban development.

Finally, we hoped to discover potential in what is missing from the discourse. Each student identified a rather unexplored form of vitality and made propositions—on a given lot and later in a neighborhood of their own choosing—to reframe development beginning with and growing out of the student’s unique framework.

Locating Vitality Drawing Series

Examples above by Kelsey Vitullo and Wendy Stradley.

On a site in South St. Louis City, owners Brea and James McAnally live in a repurposed school building. They want the former playground to become an 'artist-run commons.' The students studied the property, including the closed and privately owned half-block of street which divides the school and the playground.

Students identified forms of vitality—such as pedestrian movement, volunteer vegetation, gardening and other signs of care, the layering and entropy of materials, etc.—and coded them into a mapping.

Next, the students refined their lenses by speculating on an intervention that would make their forms of vitality more seen, enfranchised, or enhanced. As the students speculated about site interventions, they had to think through iterations based on anticipated social and environmental contingencies. Each student studied their ideas through an "If/Then Drawing" series.

Wendy Stradley's proposals marked the layering of human-made materials and the entropy which helps visualize time between periods of care and engagement.

David Eslahi's sidewalk, fence, sign, and displacement proposals, interrogating property and human agency.

1:1 Scale Interventions

Next the students chose one of their proposals based on the potential to mark and enhance their chosen form of vitality.

Tom Klein's 'stoop vitality' intervention.

David Eslahi's movable fence intervention.

Locating Vitality in the City

By mid-semester, the students were asked to install their projects and also expand their lens to map vitality in a district or the whole City of St. Louis.

Tom Klein's 'neighborhood vitality' map represents observed social interactions documented through weeks of walking and taking field notes.

Wendy Stradley's maps represent the accumulation of material through time, locating the last three surviving water towers as prime examples of how human building, entropy, and preservation reveal narratives of human will in a declining city.

Urban Development: Landscape Strategies for Existing Vitality

The students chose to either work on a landscape strategy for a neighborhood or propose three pilot sites for strategic development. Final projects engaged vacant lots and their potential for development through inexpensive stimulation of ecological processes, stoops and the public right of way, reconsideration of barriers, and the development of critical lenses for landscape preservation.

Tom Klein's began with neighborhood research, but narrowed down his site to a block with income diversity and other signs of gentrification. He then designed an event, called Stoopfest, that would encourage people to be outside interacting with each other from their stoops and through visiting others' stoops.

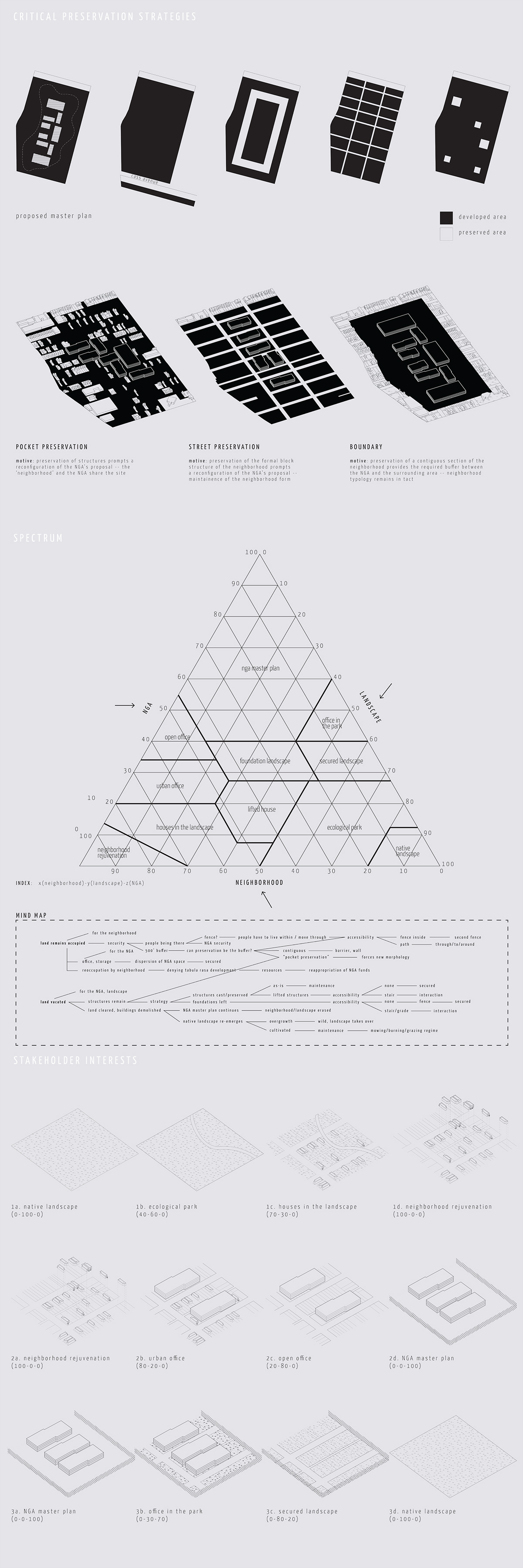

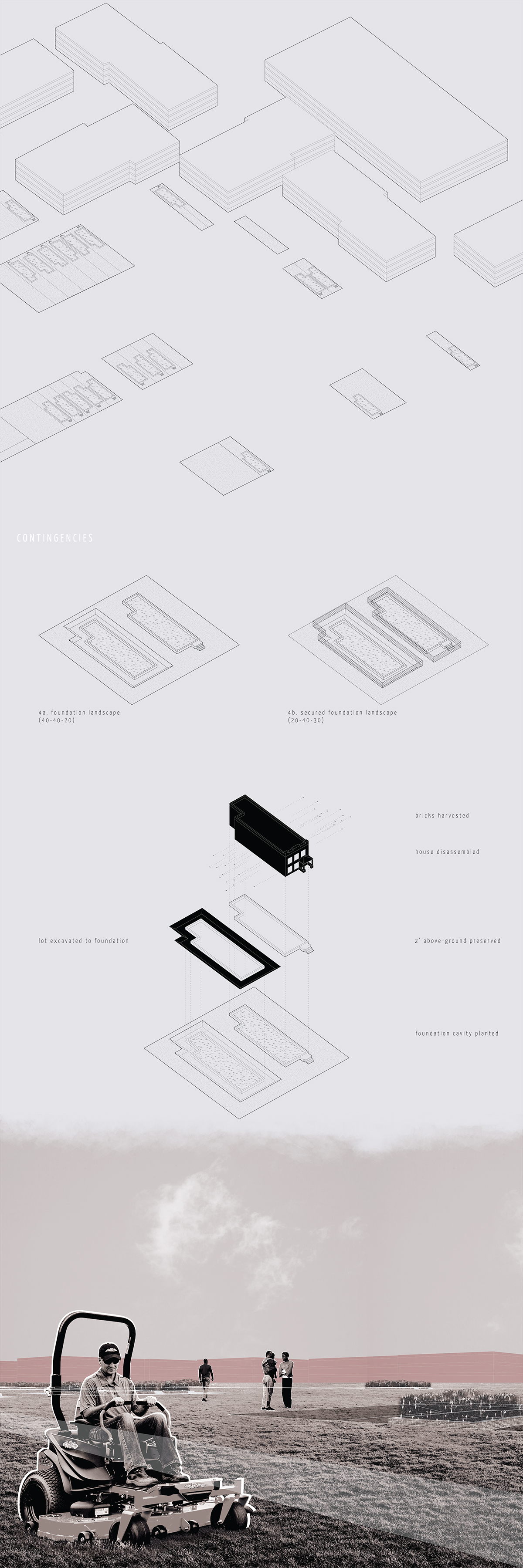

Micah Macaulay's project explored the advantages and disadvantages of various forms of preservation at the site of the controversial development of the NGA's new headquarters in St. Louis.